The Paradox of American Urbanism

In her landmark book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, Jane Jacobs draws battle lines between two radically divergent visions of American urbanism. She decries “modern orthodox city planning” which had emerged in response to the advocacy of diverse figures like Ebenezer Howard, Sir Patrick Geddes, Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and others. Their vision of a healthy modern city integrated large quantities of open space into the built environment and allowed natural landscape to be prominent, if not dominant. Leading American urbanists in the mid-20th century, like Lewis Mumford, Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Catherine Bauer, had sought innovative patterns of land use and building form which embodied a social and cultural idea of living in a symbiotic, integrated relationship with natural open spaces.

Jacobs condemns this direction for its “monotony, sterility, and vulgarity,” observing that, “Decades of preaching, writing, and exhorting by experts have gone into convincing us and our legislators that mush like this is good for us, as long as it comes bedded with grass.” She offers quite the opposite vision for emerging American urbanism. She advocates the traditional city of streets, sidewalks, small blocks, tight building fabric and mixed-use. She declares that this formula will work because it has worked and should not be tampered with. Jacobs’ critical voice was joined by contemporaries like Kevin Lynch, Gordon Cullen, and Edmund Bacon, all of whom admired, investigated, and learned from the traditional city and wrote influential books in the 1960s. Although certainly less vitriolic than Jacobs, their perspectives are nevertheless clearly critical of the emerging modern American city. Strongly influenced by this new generation of urbanists, the latter decades of the 20th century saw a somewhat begrudging return to lessons learned from European urban fabric and its reincarnations in the densest of 19th and early 20th century American cities.

In fact, though both of these polar visions outlined by Jacobs offer genuine and appropriate inspiration for contemporary American city-building, neither has been the kind of panacea envisioned by its advocates. American cities seem to be inherently paradoxical and resistant to pure solutions.

The landscape-dominated vision of Frank Lloyd Wright, Clarence Stein, and Lewis Mumford resonated in the wide-open spaces of the American Midwest, South, and West. It offered individual freedom of expression, a wide potential range of diversity in building form, and a specialization of land use that fit well with a legal system based on individual property rights and with a market-driven economy. It provided room for high-speed automobile travel and a decentralized lifestyle rooted in the single-family house. It empowered the individual as the fundamental unit of society.

But this landscape-dominated urbanism failed to fulfill other expectations of American society. In its non-hierarchical looseness it did become “mush,” to use Jacob’s term. It lacked identity – a “sense of place.” Without more containment of space, there was a dearth of identifiable public gathering spaces. A collection of object buildings did not promote a sense of community and shared turf. The genuine paradox of American culture – its democratic reverence for the individual alongside an emphasis on community and solidarity – foiled the success of such a pure, clear vision.

The more traditional urbanism of Jacobs, Lynch, and Bacon likewise offered a powerful consonance with American culture in its creation of a network of continuous public spaces where citizens could exert a collective identity and where commerce became a significant force. Its creation of axes, monuments, and landmarks resonated with an American sense of pride and identity. It gave particular opportunities for cultural icons and emblems. This vision also fulfilled an American need to grow deeper roots. It advocated integration of old and new, rather than starting with tabula rasa.

But, this pure, vociferous vision failed in striking regards as well. It seemed inherently incapable of integrating the automobile without losing its most cogent assets. It defied a real estate market and land development economy that is inherently piecemeal – not holistic. It suggested a conformity and stifling of individual expression that often seemed forced, fake. The varied, even contradictory, nature of American political, economic, and social culture, again, defied such a pure vision.

Over the last two decades we have worked on a number of projects in downtown Austin wherein we have tried to deal with the paradox of American urbanism in a very particular and responsive way. We have sought inspiration from both poles of urbanism proffered in the last half of the 20th century, but have tried to develop a new hybrid from them which would be more useful in addressing real, tangible cultural and environmental needs.

AUSTIN AS A CASE STUDY

Austin has offered an almost ideal context for this experimentation. It is a quintessentially American city. Founded in 1839 and conceived to be the Texas state capital from its inception, the city has a rich social, cultural, and political history. Its population has traditionally been well-educated and civic-minded with a keen awareness of the value of the physical environment and its profound effect on a community.

From its inception, the plan of Austin was conceived as a juxtaposition of powerful natural forces and a well-defined urban form. The site selected for the new capitol of the young Republic of Texas was chosen for its strong landscape character. Rooted at its southern end by the Colorado River, the site was framed on either side by two prominent bluffs about a mile and a half apart. At the base of each bluff was a creek – Shoal Creek at the foot of the western bluff, Waller Creek at the bottom of the eastern one. Between the two bluffs the ground rose gradually from the river northward to a hill located a bout equidistant between the strong edge features. The committee that selected the site immediately envisioned the capitol of the Republic on the hill top, framed by nature’s bookends on either side and facing down toward the Colorado River.

In 1839 Edwin Waller laid out the first plan of the city. He divided the east/west space between the two bluffs into 14 blocks delimited by 15 streets, the center one of which was named Congress Avenue. Wider than the rest, it aligned with the center of the hill intended for the capitol. The easternmost street was named East Avenue and the westernmost one West Avenue. The rest of the north/south streets were named for Texas Rivers – the westernmost being Rio Grande, the western boundary of the republic, and the easternmost being Red River, at the opposite end of its territory. In the north /south direction, Waller laid out the same 14-block dimension delimited by 15 streets. That meant the new grid stretched north of Capitol Hill a few blocks. The southernmost of these east/west streets a long the river was named Water Street. The one on axis with the hill was made a bit wider, like Congress Avenue, and was called College Avenue. The rest of the east/west streets were named for Texas trees-Mesquite, Pecan, Live Oak, Peach,

etc. (Later, the streets would become numbered.)

Four individual blocks in the grid were designated as greens or public places. These were evenly dispersed in the area between College Avenue and the river and on either side of Congress Avenue. The four blocks that occupied the top of Capitol Hill were bundled together in a much larger superblock which would provide a green setting for the Capitol Building. The 1839 plan of Austin neatly described a confluence between forces of nature – the river, the bluffs, the creeks, the hill, etc. – and a geometrical urban fabric – the 14-block by 14-block grid, the axes of Congress Avenue and College Avenue, the axial terminus of the Capitol Building, the geometrically spaced greens, etc. Even the grid of streets itself, the strongest of urban gestures, acknowledged its counterpart by naming its elements for natural features – rivers and trees.

The dialogue between natural form and urban geometrical form began almost immediately in downtown Austin and continues today. The grid never really managed to conquer the creeks. Bridges were not built because of expense or because of the threat of being washed out, so streets around the creeks became erratic and discontinuous. Evcntually, along Shoal Creek to the west, the tight geometrical urban fabric implied by the grid became a loose series of green spaces – Duncan Park, House Park, and Pease Park. A similar pattern occurred to the east with Waller Creek generating Palm Park and Waterloo Park.

The Jane Jacobs ideal of streets, sidewalks, small blocks, and tight building fabric got inevitably and beneficially compromised by the intervention of exactly what she decries – large quantities of open space allowing natural landscape to be prominent if not dominant.

The story of the development of downtown Austin is littered with examples of this paradoxical coexistence of two well-defined and warring camps of urbanism. It seems the populace, as well as the forces of both nature and economy, genuinely demanded a constant standoff between the two. In the planning and urban design work as well as in the architectural projects we have done in Austin, a recognition of the productive tension of this dichotomy – inherent in the earliest plans of the city and broadly evident in citizens’ sentiments today- has been both inspiring and challenging.

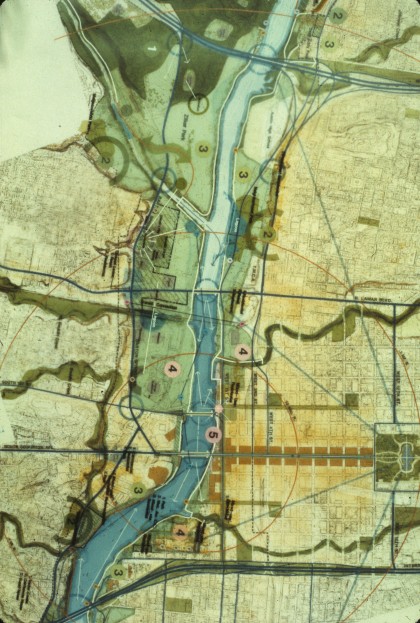

THE TOWN LAKE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN

The Town Lake Comprehensive Plan (TLCP) was done as a joint venture between Lawrence W. Speck Associates and Johnson, Johnson and Roy Landscape Architects and was completed in 1984. This two-year effort was the largest planning project ever done by the City of Austin and involved proposals for a 7.5-mile-long segment of the Colorado River running through the center of the city. The project included urban design recommendations for city fabric on both sides of the river as well as proposals for land acquisition and parks and public space development in the river corridor.

For over a century, the city had turned its back on the flood prone river, lining its swampy banks with clay quarries, rail yards, a water treatment facility, two power plants, and a motley assortment of low-density warehouse buildings. Creation of Longhorn Dam in 1952 stabilized the river’s water level and established Town Lake as a safe and scenic body of water, While several extraordinarily attractive amenities developed prior to the dam were located in close proximity to the lake (Zilker Park, Barton Springs Pool, Deep Eddy Pool) the city had still not, by the early 1980s, managed to reorient itself to capture and consolidate a cohesive riverfront.

The new plan envisioned Town Lake as the heart of the city – a real urban hub where civic life and activity were concentrated. It imagined an urbanism fully committed to interaction and social gathering which might not be limited in physical form to the street, the square, and traditional urban parks. It conceived outdoor activities like walking, biking, boating, swimming, and sports as potential contributors to the urban scene. It integrated places for picnics, outdoor concerts, and casual dining with more high-brow cultural venues like museums, theaters, and performance halls. It offered opportunities for an urbanism which was both densely built and primitively natural in radical juxtaposition. It embodied a way of life that resisted pure stereotyping – that accommodated a broad range of citizen interests and perspectives.

The urbanism depicted in the TLCP embraces principles of both the modernist landscape-dominated attitude toward city-building damned by Jane Jacobs and her followers in the last decades of the 20th century, as well as tenets of a more building-dominated approach to creating city fabric which Jacobs and others advocated. It is comfortable with a weaving together of towers and other solitary buildings set in open space alongside tightly delimited urban rooms framed by well-coordinated facades of multiple buildings working together. It accepts the appropriateness of “one-off” object buildings as well as advocating, at times, the creation of highly regulated ensembles. It celebrates both individuality and the collective good. It balances the inevitability of a convenience-minded, car-oriented culture with the civility and graciousness of well-designed pedestrian environments. It accommodates an economic and financial structure which is frequently focused on singular uses and markets, but, in the end, revels in mixed use by disallowing too much of any singular use in anyone place and encouraging an overall balance of residential, office, commercial, and cultural/institutional uses.

One of the earliest steps in conceiving the TLCP involved outlining five different kinds of outdoor spaces we felt essential to include in the center of the city. Each was intended to add a dimension of experience of public space which would enhance overall life and activity.

Preserves were intended to locate, in the very heart of the city, some land that would be left in as natural a condition as possible. There was a desire not to exclude native flora and fauna of the region even in this area of densest human population. By retaining natural environments virtually in accessible to humans, ecologies could be maintained which are essential in the larger balance of species interaction. It would not be likely, for example, that the largest urban bat colony in the world, which inhabits downtown Austin, would survive if there were not some substantial areas of dense vegetation and a full range of animal and insect species nearby. Carefully delineated preserves were therefore distributed throughout the length of the TLCP.

Sometimes the preserves were linked to research or education functions as in the case of land around the Nature Center or the large University of Texas Biological Research site (prime waterfront land which is committed to studying animal migratory patterns around the river). Other times, the preserve is made virtually inaccessible to anyone as in the case of some parts of Colorado River Park. Buildings and even trail improvements are pretty much excluded on preserve land.

Neighborhood Parks are intended to link Austin’s thriving in-town neighborhoods directly into the life of downtown and Town Lake Park. One of the very healthiest features in central Austin is the presence of a series of well-established neighborhoods that ring the urban core. They a re widely varied ethnically and demographically, and generally have houses from a range of eras – usually beginning in the 1920s or 1930s, but some going back to the 19th century. Of particular interest in the TLCP were Tarrytown, Clarksville, Rainey Street, Old West Austin, East Austin, and Govalle north of the river, and Bouldin Creek, Travis Heights, and Riverside south of the river.

The idea of the neighborhood parks was to create little enclaves that belonged quite solidly to the neighborhoods with their activities focused on the particular ethnicity or demography of local neighbors. Fiesta Gardens, for example, focused on celebrations and occasions particular to Hispanic and Mexicano East Austin adjacent to it. Stacey Park in Travis Heights was to link local pool and recreation facilities out to the broader Town lake Park. Tiny Eilers Park in West Austin was to provide picnic and playscape area for families living nearby but also was intended to create an outlet to the larger Hike and Bike Trail around the lake.

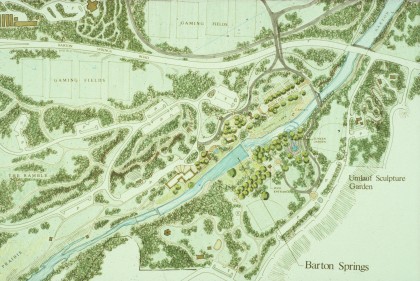

Community Parks were conceived as larger citywide facilities which would draw people from all over Austin to sophisticated recreation areas, sports venues, or individual activities. The Hike and Bike Trails were to link all the Community Park spaces together. Several spectacular icons were featured in the Community Parks. Barton Springs Pool, built in the 1930s in Zilker Park, sets a benchmark for great urban recreation spaces with its distinguished pool house and scenic sunning slopes. Deep Eddy Pool creates a mecca for family recreation with its enormous children’s pool as well as its serious sports swimming area nestled under towering cottonwood trees.

Part of the idea of these Community Parks was that in Austin the kind of “seeing and being seen” that occurs in Italy on the piazza or in Mexico on the plaza might happen here on the Hike and Bike Trail. Teenagers “scoping each other out” might occur just as likely in the promenade a round Barton Springs Pool as in a kind of cafe society on a boulevard one might have found in a tradition al European city. The same kinds of community – building urban places that create a powerful downtown identity and sense of place might be equally potent in a fresh and more particular kind of “urban” setting here.

The attitude in all Community Parks was to take a lesson from Barton Springs and Deep Eddy Pools and to emphasize scenic aspects over the creation of just “facilities.” Lighted sports fields and spectator stands were relegated to a very few areas, keeping the predominant feeling soft, green, and park-like.

Cultural Parks were intended to be settings for activities that would, in a strictly Jane Jacobs kind of urbanism, be located on the square or terminating the axis or spilling onto the city streets. But in Austin it seemed like cultural institutions such as a performing arts center, a community events center, a Mexican-American cultural center, a community arts center, a nature center, a science museum, etc. might just as appropriately occur in a symbiotic relationship with an active green space as with a street or plaza. These kinds of institutions were seen as opportunities to bleed the boundary between recreation and cultural activities in the form of outdoor concerts, outdoor musicals, music festivals, and even fundraisers for community causes like the Capitol 10K run.

Though there was a strong commitment to some cultural events like the Paramount Theatre being on a main street like Congress Avenue or the Austin Museum of Art being on a public plaza like Republic Square, there was also a sense that having cultural institutions in a wide range of settings could enrich the cultural life of a city. A wider range of events might be germinated and a broader range of people might get involved. Buildings to house cultural events in a park context were imagined to be pavilions in open space, giving a range of opportunities for architectural expression. (It is sad to see institutions trying to make their mark by plopping “object” buildings in “fabric” situations. Isn’t it better to have some places where “object” buildings make sense?)

The life of a cultural park would be urban, but informal. There would be mixed use, but the uses might be dog-walking, picnicking, soccer games, and antique shows, rather than the more conventional retail, office, and residential uses. This pattern acknowledges the broader range of late 20th -century/early 21st -century life and the powerful role of leisure and recreational activities in our lives – especially in a city like Austin.

Urban Waterfront is the designation given to open spaces that were to be strongly defined by building edges. This is where the traditional realm of street, sidewalk, and square resides – where spaces are closely contained. In the district of the TLCP this was primarily in the stretch where Town Lake Park runs through the original city grid. Here, the notion was that a strong architectural edge should be created which would be of sufficient scale to create a kind of “room” of park space but not so gigantic as to dominate the river and park edge. This boundary would best be relatively continuous, taking a cue, perhaps, from the extant scale of the Seaholm Power Plant (a beloved and powerful relic just west of the point where Shoal Creek empties into Town Lake). There should not, it was recommended, be any more towers at this edge.

This strong urban boundary was intended to create a striking dialogue between the tight, gridded urban fabric of downtown and the lush, green, natural park space. The green of the park space was meant to filter into downtown via five routes. Shoal Creek and Waller Creek would draw loose meandering park space into the grid eroding it and providing interesting sites for opportunities not available elsewhere in the tight street fabric. In addition, two of the north/south streets, Guadalupe Street on the west side and Trinity Street on the east side, were designated “green fingers.” Though they would maintain their linear, geometric form, they would get more street trees, more pocket parks than neigh boring streets. They were selected both for the fact that they ran uninterrupted from the waterfront deeper into the city than their neighbors and for the fact that they ran alongside the four blocks originally designated for parks in the 1839 plan finally, the fifth penetration of the park presence into the tight downtown fabric would be Congress Avenue – a very broad, tree-lined processional culminating in the lush parkland around the Capitol Building.

All of these open space types – the Preserves, Neighborhood Parks, Community Parks, Cultural Parks, and Urban Waterfront – contribute a particular dimension to public life in the city. They also exercise a full breadth of relationships between buildings and the natural environment. Much of the effort of creating the Town Lake Comprehensive Plan went into locating where what open space type might be appropriate through the 7.5 -mile length of the Town Lake Corridor. As with all such planning efforts, there is no such thing as full implementation, but the TLCP has made a striking mark on the city in the 20 years since its adoption, not least in several landmark building projects that we have been involved in which follow.

AUSTIN CONVENTION CENTER

Three years after the completion of the Town Lake Comprehensive Plan we were hired by the City of Austin to do final site designation and design for a new Austin Convention Center. Though a general location for the convention center in the lower part of downtown had been suggested in the TLCP a great deal of work was required to outline a quantity of land and exact location which would not only serve the initial needs of the convention center, but could also accommodate future expansion.

The commitment to place the convention center in a neglected part of downtown was critical. The project was intended to seed downtown development. The site eventually chosen reinforced the commitment on the part of the city’s hotels to stay downtown by locating near them. It significantly boosted a flagging Sixth Street Entertainment District, stimulating it to become one of the most valued assets of the community. And, in just over ten years, it helped transform over 20 blocks of derelict buildings and open parking lots into a district with not only the original and expanded convention center, but also two large new hotels, several renovated and new multi-family housing projects, and a dozen or so restaurants – mostly in renovated buildings.

The southeast corner of downtown where the site was located was an eclectic melange of disparate elements. Two blocks east of the site was Interstate Highway 35, a mammoth elevated freeway which was cut through downtown Austin in the 1960s. Two blocks southeast was the Rainey Street neighborhood, a small but sweet and neatly preserved enclave of tiny single-family houses on tree-lined streets. Two blocks south of the site was one of the very nicest parts of Town Lake Park where Waller Creek joins the river. The bluffs were dramatic, the banks wide, and the trees huge in this part of the park. Two blocks to the west were high-rise office towers on Congress Avenue. Two blocks to the north was the Sixth Street Historic District, struggling to become an entertainment focus for the city.

The immediate surrounds of the site were also strikingly divergent. The four-block tract was bounded on the south by Cesar Chavez Street, a major east/west connector and something of a ceremonial street in the city. On its west was Trinity Street, a thoroughfare with little automobile traffic but which had been slated in the Town Lake Comprehensive Plan to become the Trinity Street Green Finger. It was intended to make a strong pedestrian connection between the Sixth Street Entertainment District to the north and Town Lake Park to the south. The northern boundary was Third Street-another street with very little traffic which, in fact, was planned to be closed when expansion occurred. The eastern edge of the site was Red River Street which had excellent north/south connectivity for vehicles but little actual traffic. Across Red River was an enclave of tiny historic wooden buildings and Palm Park. Clipping the southeast corner of the site was Waller Creek with its steep limestone banks and big mature trees. Across the creek was a historic building which once housed Weigl Iron Works, a source of extraordinary German metal craft in the early 20th century. The little metal building had for many years been a popular barbeque restaurant.

The building type we were placing on this complex and provocative site is not one generally considered to be urban-friendly. As was noted in an article in Progressive Architecture shortly after the Austin Convention Center was complete, these institutions are generally characterized by “vast exhibition/meeting rooms, smaller multi-purpose rooms, and prefunction areas, jammed into featureless, windowless volumes devoid of relation to their surroundings.” The PA article went on to describe our very different approach:

Here, in a new building on a site open to all sides, yet oriented to different urban and landscape conditions, one can articulate the parts and put them into dialogue with their surroundings… We see that a convention center need not be one great mass, but rather something of a village in itself. Spaces are differentiated both with reference to their own use or place in the internal organization as well as in relation to site conditions. These changes in form are paralleled by changes in materials. Yet this appears not as a nostalgic or historicizing “village,” but as a genuine rethinking of the organization of large systems in elements that consider the person and the more intimate scale of the urban landscape.

We placed the largest-scaled spaces, the exhibition halls, in the center of the site and wrapped them with the “village” of smaller-scaled functions facing the streets and the creek around the perimeter. Each programmatic element in the “village” finds its own shape, form, and material treatment in response to its function and location. Various parts of the building honestly express the broad range of activities that occur within. Lobbies, stairs, escalators, etc. are allowed to take on their own individual identity on the façade as well. As all of the various elements add up, they create a streetscape which is similar in richness, scale, and diversity to what one finds on nearby Congress Avenue or Sixth Street. The kind of articulation that might have been created by a drugstore next to a haberdashery next to a hardware store is not so different in general character from that created by a lobby next to a meeting room next to a prefunction space. Without being cloying or condescending, the building becomes a natural extension of the existing city.

Various functions of the convention center are matched with varied conditions on the site. The more relaxed functions of the cafe, bar, banquet hall, lobby, and terraces are stretched along the more casual edge of the site – along Waller Creek. This part of the building is loose and faceted, creating a relaxed feeling appropriate to the functions. It skips in and out, reacting to the mature trees and the bend in the creek. The building is low in scale here, stepping gradually up from creek bed to terrace to lobby to banquet hall. It does not overpower the scale of the landscape or the little historic buildings around. Materials are mostly a random ashlar stone, which is sympathetic to the shapes, colors, and textures of the limestone creek bed.

As the building transitions from the Waller Creek side to the Cesar Chavez Street façade, the loose facets of the terraces become more regular, forming a tall polygonal lobby. This strong feature anchors the east end of the Cesar Chavez Street façade and is roughly matched by a similar rectangular lobby on the west end. Here, the most ceremonial functions of the building find their home on the most visible and ceremonial street in the district. The polygonal lobby becomes the primary “front door” to the banquet hall while the rectangular lobby serves a similar function for the exhibit halls. Between the two landmarks, a bank of escalators is marked by a notably vertical expression in the façade, and two-story prefunction spaces are lined by generous porches where occupants can spill outdoors for breaks between events. The porches also double as effective sun shades on this southern face.

The Trinity Street façade expresses the more everyday “workhorse” functions of the building. Various meeting rooms each receive individual treatment. The most elaborate of these is placed at the terminus of Second Street so that it gets an unobstructed view west to the Hill Country. Its large oculus-shaped window with a carefully articulated sun shade becomes a landmark in the city when viewed down Second Street. Next-tier meeting rooms occupy simple masonry volumes and have large rectangular openings onto the pedestrian-friendly Trinity Street. The more generic and subdividable meeting spaces are in a raised metal-clad box that reflects their rhythms and repetitiveness honestly. Escalators and stairs on the Trinity Street façade are marked by appropriate stepped and vertical volumes. Prefunction spaces have similar double-decker porches to those on the south façade.

The building line is varied along Trinity Street creating a series of tree-filled vest-pocket parks as a means to reinforce the intended “green finger” character of the street. Because transit stops are located here and because the convention center parking garage is a block to the west, this is a common place for everyday arrival to the building. The gentle, almost completely permeable nature of the building here contrasts with the more ceremonial approaches off Cesar Chavez Street. A deep covered loggia at the north end provides a sheltered place for meeting, greeting, or waiting for transportation.

The Austin Convention Center is marked by the genuine paradoxes of American urbanism. It is a traditionally “urban” building with facades creating edges to well-defined street spaces. It makes good city fabric. But it is also a building set in nature in some ways, reveling in the loose, enriching intrusion of Waller Creek on the downtown grid and drawing some of the lush greenery of Town Lake up Trinity Street into the city. It takes the freedom to acknowledge the disparate, sometimes chaotic nature of the American city which is often more a bout precipitous shifts and mind-boggling contrasts than about clarity or consistency. As the previously mentioned PA article notes, this is a “building that can set a pattern for civic development, maintaining the scale of Austin’s historic fabric while projecting messages not only about the city’s divisions but about its ultimately in valuable diversity.”

THE TERRACE OFFICES

Located about two miles south of the Town Lake Corridor, the Terrace Offices are perched on the side of a bluff that looks back to downtown. This project deals with an increasingly prevalent paradox of American urbanism – a medium-density office complex nested in a dominantly natural setting. In this case, the site was an ecologically sensitive, never-developed tract adjacent to a nature preserve. Because of its proximity to downtown, however, development pressure was significant.

The American love affair with the outdoors and our desire to live and work in close proximity to nature can sometimes create ironic situations. The permitted density on this beautiful, unspoiled site could easily have obliterated the very assets that made it especially appealing to begin with. The master plan originally approved by the City of Austin for site development would have created a fairly normal office park with generic boxy buildings straddling precipitous topographical changes with plenty of manicured lawns. It would have destroyed many of the mature trees on the site and exiled the kind of flora and fauna that had so amiably inhabited it.

The revisions we suggested included stringing the buildings’ long and thin parallel to contour lines and minimizing cut-and-fill. By bending the buildings slightly, we could save all of the real specimen trees and retain much of the existing topography. We also made a very strong point of leaving the “thicket” of vegetation on the site intact insofar as possible. During construction, fences were erected ten feet outside the building perimeter to keep construction spoilage to a minimum. A price tag was put on all the adjacent trees so that if one was destroyed or damaged fines could be assessed. The goal was to place this relatively dense urban element on the site with as little disruption as possible.

Impervious cover on the site was kept to a bare minimum. Access roads were made the most direct and efficient possible. A single paved area was designed to triple function as access to the garage, drop-off, and turn-around for service vehicles. The little court was even walled off from adjacent native landscape to prevent intrusion. Openings in the wall give cues that this natural environment is to be enjoyed visually, but not disturbed.

The result is a rather startling urban gesture – a powerful juxtaposition of built and native environments. Suburban accoutrements like lawns, shrubs, ornamental landscaping, and planting beds are absent. The vocabulary is tight, clean, and urban on one hand and wild, native, and natural on the other. The architectural vocabulary reinforces this notion. Stone walls begin thick and dense with small openings looking out into the near-view thicket on lower floors. As the building rises and the thicket becomes less dense, the windows increase in size inviting longer views. The top floors are almost all window, the stone piers having diminished and converted to precast concrete, inviting dramatic views across the valley to downtown.

COMPUTER SCIENCES CORPORATION

When Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) was making plans to create a large new facility for its operations in Austin, their first inclination was to look for a suburban site at the edge of the city. CSC, like most other software companies, had a history in its operations worldwide of locating in “office-park” or “campus” environments. Their expectation was to build a secure (even gated) precinct wherein several buildings and a parking structure would be set in a single-use, landscape-dominated context.

This sort of thinking about site selection had become commonplace among other high-tech companies in Austin, such as Dell, Motorola, and IBM. As these knowledge-based corporations expanded, they tended to produce multi-building complexes on the fringes of the city. The subsequent roads, utilities, housing, and other services that were required for their high-tech workforce were sprawling deep into the Texas Hill Country causing justifiable alarm among environmentalists and taxing both governmental and private sector resources as they scrambled to provide infrastructure for rapid growth. This tendency provoked some serious soul-searching as to Austin’s image of itself. The impact of rampant urban sprawl with its associated traffic congestion, air and water quality degradation, and destruction of valued scenic landscape posed a fundamental lifestyle threat in Austin and provoked vociferous political debate.

In the meantime, Austin’s downtown was enhancing its role as home to a vibrant arts and entertainment scene, but had stagnated somewhat as a home for businesses. The presence of the convention center and most of the major hotels downtown had populated the urban core with visitors anxious to bolster Austin’s vital club and live music scene. In-town neighborhoods provided enough nearby residential support to maintain dozens of good restaurants and even an upscale health food grocery. Most of the local arts organizations were committed to locations downtown drawing their patrons from all over the city. Town Lake Park had become a kind of “living room” for the metropolitan area attracting thousands of daily users to the Hike and Bike Trail and tens of thousands to special events and festivities. But there were parts of downtown where nothing happened above ground level – where density of people and activity was sorely lacking.

One of the most visible areas of this sort was a five-block district in the southwest part of downtown where the City of Austin owned most of the real estate. Mayor Kirk Watson, elected in 1997, was fond of saying, “If you asked an Austinite to walk through the downtown and point out its ugliest four or five blocks, these would be the ones.” He was committed to constructing a new city hall in this district, consistent with the Town Lake Comprehensive Plan, and to encouraging development of a mixed-use district a round it.

For many months there were ongoing discussions and negotiations between the City of Austin and CSC to see if this district might be a suitable spot for the 600,000 square feet of new office space CSC was planning. As architects for CSC, we participated fully in projecting and testing a range of possibilities for matching the very real needs of an industry based on suburban notions of office development and a downtown core hungry for an infusion of life and people who were a part of the “new” Austin economy. There was talk of a “digital district,” where CSC would be a key stimulus with housing, retail, governmental, and arts facilities working together to produce a physically and culturally rich urban ensemble.

The scheme that was eventually selected in a joint agreement between the City of Austin, CSC, and a large residential developer created two blocks of offices with retail on the ground floor for CSC, two blocks of multi-family housing with retail on the ground floor for the developers, and one block for City Hall and its plaza. City Hall would occupy the focal point at the end of Drake Bridge with its plaza toward Town Lake Park. CSC would occupy the two blocks on either side of City Hall, creating a frame for the public plaza and what was hoped would be an iconic civic building. The multi family housing would occupy the two blocks behind the CSC buildings on Second Street. Retail on the ground floor of all of the buildings would orient strongly toward Second Street, which would become a new pedestrian-focused retail core at the heart of the district.

The City of Austin committed substantial funds to infrastructure improvements (though still far less than it would have cost to produce suburban infrastructure for this size development). Their incentives included a “Great Streets” program to refurbish all streets and sidewalks in the district and the provision of a central heating and cooling plant which would provide substantial energy savings. Even with such incentives, however, this was a difficult and rather daring commitment to make on the part of CSC. They had to be convinced that they could get all of the amenities they were accustomed to in a suburban location but with some value added for being in the heart of the city.

Three perceived assets of suburban locations that had to be captured on this urban site were security, ease of access (particularly by automobile), and views. Because there is a great deal of proprietary information involved in the work CSC does (both in terms of CSC’s own research and development tools and in terms of their client’s data), it was critical that a secure work environment be maintained. This was important not only within a single unit or building, but within the entire complex. Data, equipment, and machines had to be able to move freely around the whole facility without a breech of security. On a suburban site this was generally accomplished by creating a secure compound that could be gated for privileged entry.

On the downtown site we solved this problem in two ways. First, we made the lobbies far more important places than they would normally have been. They became, not only places for screening people for entry, but also spaces where interactions with people from outside could occur in a non-secure environment, thus avoiding screening. It was critically important, however that these lobbies not seem like heavy-handed security barriers. Just as the drive along a curving wooded road makes a guard station seem less threatening to the authorized visitor in a suburban environment, so something had to be done in much less space to accomplish the same civil and gentle fee ling of security here.

A second measure taken to achieve an internal secure environment was to build a tunnel connecting the two buildings a block apart from each other. Intentionally not convenient for everyday movement of workers from one building to the other, the tunnel provides only for transfer of secure documents, equipment and machines. All other movement between the two buildings actually benefits from and contributes to the urban street-scene of the district.

Ease of access to and from the site, especially by automobile, had to be accomplished at least as easily as on a suburban site. There was to be a great deal of coming and going to the buildings at all hours of the day by CSC employees, who travel a great deal and have frequent meetings with clients and others off-site. Parking areas needed to feel safe and routes from parking to work spaces needed to be clear, simple, and direct. The solution we chose brought the parking directly into each building via a secure entry portal. Access could then be gained directly into work space via card-key without going up or down in elevators. This approach actually addressed CSC’s concern much better than is done on most suburban sites. The density and compactness as well as the higher price of urban land provoked a more efficient solution with smaller travel distances.

Many suburban sites in Austin are blessed with excellent views in virtually every direction. For many high-tech workers, a view to a serene natural environment from one’s workspace is a prized asset. It was important to prove to CSC that we could match the view potential of a suburban site in a downtown environment. Given the availability of Town Lake Park on one side of each site we were able to maximize views in this direction and thus gain the sense of distance, big sky, greenery, and water which is so treasured in Central Texas.

In addition to capturing these assets commonly available at the edge of the city, CSC understood that they got substantial bonuses for their employees by being downtown. They could participate in a lively mixed-use environment which offered options for lunchtime or after-work activities far richer than what is available in the suburbs. There would also be distinct options for living and working downtown and avoiding commuting altogether – even within the “digital district” itself. But it is important to understand that the kind of “Jane Jacobs urbanism” described earlier was not compelling enough to bring CSC downtown on its own. It was a distinctly new kind of urbanism strongly incorporating parks, recreation, and open space that attracted CSC back to the core of the city. It was the accommodation and taming of the car that made this kind of urban environment work for them. It was the acknowledgement of new business and security realities very different from those that shaped traditional cities that made a downtown location make sense for this emerging industry.

It is fundamentally important that these issues be engaged and that we find a way to attract the industries that have fled to the suburbs back to the city center. It is romantic and nostalgic to think that the ingredients that went into a 19th- or early 20th-century core are going to recreate themselves in the 21st century. As industries, businesses, and economies change, so must urbanism find new forms to reflect new cultures. One of the most exciting things about some younger (and growing) American cities like Austin is the opportunity they represent to create new urban forms and new urban social chemistry.

The architecture of the CSC project emerges overtly from its urbanism. The buildings have solid, simple massing reflecting the powerful grid of downtown. Their six-story height is intended to create a clear edge to Town Lake without overwhelming the scale of the landscape – just what was stipulated in the TLCP. They create a frame for the axis of Drake Bridge and bookends for the new City Hall and Plaza.

The westernmost building is notched on one corner to preserve the only significant preexisting structure on the site-the mid 19th-century J. P. Schneider Dry Goods Store. The simple rectangular volume of this historic structure, typical of what was once found in much of downtown Austin, is made of a local buff-colored brick laid up with elegant and straightforward tectonic clarity. These buildings take some of that same tectonic clarity and apply it at a larger scale to contemporary construction technology. Hefty masonry piers made of load-bearing Leuders Roughback stone create a general exterior armature for the buildings. The Roughback stone is used in large blocks and revels in the wide range of color variation – from creamy buff to caramel – inherent in its geological formation. Horizontal precast spandrels tic the piers together on the lower floors.

Placed substantially back from the face of the masonry, an intricate glass curtainwall interlocks with the stone piers. The glass is set in two different planes to give relief and to emphasize its thinness. A complex layering of colors in the glass – from milky white to a deep watery green – animate the façade further as well as help to ameliorate visual differences between lower floor-to-floor heights in the garage and taller ones in the office areas. A copper sunshade of rather heroic scale helps to terminate the piers and readdress the horizontal line of the river’s edge.

These buildings are robust urban fabric. As commercial structures, they make no claim to the kind of object quality that, in this district, needed to be reserved for City Hall. They are constructed of materials that integrate them inextricably into their surroundings. The Leuders limestone, by its color and texture, creates a rich, warm dialogue with both the limestone bluffs of the river nearby and the historic remnants of old downtown Austin. The deep green glass has the same reflectivity and color as the river’s surface. But both stone and glass are also very particular and identifiable as themselves. They are not neutral or anonymous. They have their own distinct character.

Even the interiors at CSC owe much to the urban context. A small courtyard at each building’s entry, facing Town Lake, pulls a bit of the park space onto the site. The entry lobbies extend that gesture with their backlit glass walls that draw the shimmery lightness of the river right into the building. These large, carefully programmed spaces reinterpret the loose, interlocking spaces of the park in sumptuous, tactile materials – several kinds of greenish glass, stucco lustro piers in deep, rich colors, intricately grained wood. The lobbies are inspired by the park space, but do not mimic it literally. They just have a feel that is compatible.

Upstairs spaces are all about the view with 13-foot windows at the perimeter that draw the eye outward. Open plans and glass interior partitions where rooms are required, bring the sense of outdoors deep into the building. Special facilities like lockers and showers facilitate employees’ taking advantage of the Hike and Bike Trail and other recreational amenities of Town Lake Park.

As Architectural Record noted in a feature shortly after the buildings were completed, “The strength of the CSC complex is its urbanity. Its buildings were conceived as parts of a civic and commercial landscape, not as discrete, grandstanding objects. They do not strut or preen… In an age of steroidal architecture, you have to applaud that.” The CSC buildings advocate an urbanism that reflects the paradoxes of the contemporary American urban scene naturally and since rely. They are a genuine attempt to make architecture grow out of larger concerns for the city and thereby make it a tool for the creation of an appropriate and meaningful urbanism.

AUSTIN CITY LOFTS

As early as May 1984, in a planning study done by Denise Scott Brown, the lower part of Shoal Creek, near its termination into Town Lake, was proposed as a high-density residential district. The Town Lake Comprehensive Plan reinforced that direction. Ideal for multi-family housing, the district is bounded to the west by an area containing shops, restaurants, health clubs, and a large grocery store, rare for downtown environs. Just to the east is Austin’s central business district with its requisite office towers, but inhabited at much of the street level by a lively entertainment district. North along Shoal Creek is the two-mile-long, meandering Pease Park that stretches up into several of the most sought-after in-town neighborhoods in the city. Just to the south is the seven-mile-long Town Lake Park with excellent recreational amenities.

This is an almost ideal context in which to weave together the landscape-dominated urbanism with towers placed in large open spaces, and the more building-dominated city fabric with well-defined streets and contained spaces described in the early part of this essay. The site for Austin City Loft’s, a 14-story, 82-unit multi-family residential building, is just at the edge of the original Waller grid and located on Fifth Street, a major arterial entering downtown from the west.

We chose to tie the building strongly to the downtown grid by aligning it with the Waller Plan, even though fifth Street skews a bit as it extends off the original city plat. We emphasized the containment of the street with a three-story, load-bearing masonry wall, its height as well as its materiality matching the pedestrian scale of much of downtown. Retail space on the ground floor as well as the project’s entry lobby lines the Fifth Street façade.

The building demurs to the landscape character of Shoal Creek immediately to the west. It sets back from the waterway and Hike and Bike Trail to create a pool and recreation area with an outdoor entertainment space. The scale is broken down by varying the volumes of the building and by utilizing a range of materials and treatments – stone, copper shingles, concrete, corrugated metal. This edge of the site, which is a full story below street level, is soft and green. Huge tree canopies dominate vistas. The building becomes a tower set in a park.

Even inside, the design of living spaces revels in this duality of landscape and city, openness and containment. Lower units are nestled into treetops. Upper units have spectacular views both to the city and to the hills and the greenbelt of Town Lake. Everyone has generous outdoor spaces – terraces, outdoor rooms, and balconies. Life here embraces the vital, enriching paradox of American urbanism.

Featured In

Design Awards

- Downtown Austin Neighborhood Association Award

- Austin Chapter AIA Merit Award

- Austin Commercial Real Estate Award

- Austin Chapter AIA Honor Award

- Texas Society Of Architects Design Award

- IIDA Texas/Oklahoma Chapter, Residential Design Excellence Award (Speck Loft)

- Dream Home Awards, Best Interior Design For Condominium/Loft

- Dream Home Awards, Best Condominium/Loft

- Austin Commercial Real Estate Award

- Associated Builders & Contractors Excellence Award

- Associated General Contractors Building Of The Year

- Austin Chapter AIA Honor Award

- Texas Society Of Architects Design Award

- Austin Business Journal Best Real Estate Deal

- Associated General Contractors Award

- Society Of American Registered Architects Design Award

- Downtown Austin Alliance Design Impact Award

- Austin Chapter AIA Honor Award

- Texas Chapter American Society of Landscape Architects Design Award

- American Society of Landscape Architects National Design Award

- Austin Commercial Real Estate Award