Pennzoil Place

No building in Texas has created more excitement in the process of its coming to being than Pennzoil Place did in Houston in the early 1970s. Already graced by such refined modern works as Mies’ Museum of Fine Arts and SOM’s Tenneco Building, Houston was ready to break away, to raise buildings which would reflect its ambitions and vitality. Pennzoil gave a palpable presence to the city’s energies. Here was a building that expressed in physical form the free-wheeling, chance-taking, wildcatter character of Houston. It immediately became a symbol for the city and a sign of things to come for Texas commercial building.

Three major actors were responsible for the daring and the quality of Pennzoil Place – Pennzoil Board Chairman Hugh Liedtke, Houston developer Gerald D. Hines, and New York architect Philip Johnson. The building, as it stands, is a monument to the resolve of all three.

Liedtke and his company had made a decision in 1970 to consolidate their scattered offices in a centralized location in downtown Houston. Ill-equipped to plan and build the building itself, the Pennzoil company called on Hines’ expertise as one of the largest developers in the country and one who was known for producing such quality Houston projects as One Shell Plaza and the Galleria Shopping Center. Liedtke made it clear to Hines that Pennzoil “didn’t want ‘just another building: particularly a modern wedding cake or a cigar box” (“Is ‘Wow!’ Enough?” Progressive Architecture, August 1977, p. 66).

Hines called on iconoclast Philip Johnson and his partner John Burgee to produce an architectural expression which would satisfy Liedtke’s desire for a distinctive, identity-producing building while at the same time satisfying his own financial requirements for the project. Pennzoil was to be the major and controlling tenant in the building, but it would require only half of the 1.6 million square feet which economics dictated the site should bear. The remaining commercial lease space had to fit into the requirements of the speculative office market at the time.

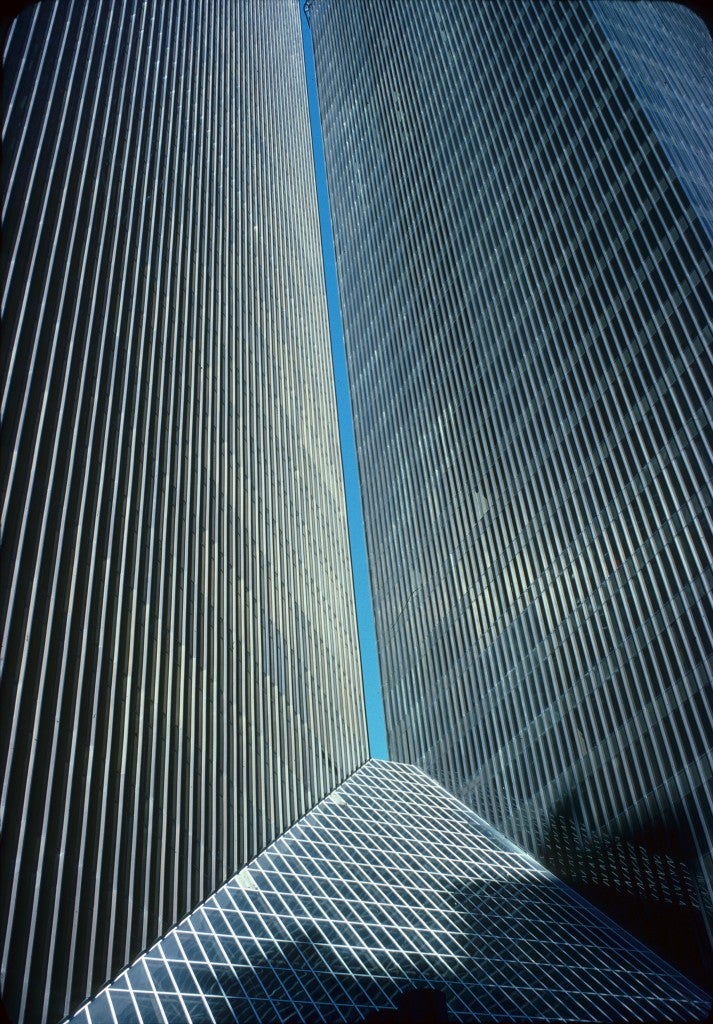

Despite the project’s requirement for high visibility and very high density, Johnson and Burgee came back to Hines and Liedtke with a solution that would notably not be the tallest building on the Houston skyline. They opted instead for an ingenious twin-tower scheme which, even though it covered almost three-quarters of the block with tower footprints, produced adequate light and view from all lease spaces. This was accomplished by slicing the buildings at 45° angles to create trapezoids in plan and placing them very close together – only ten feet apart at one point. The remainder of the block, outside the tower footprints, was to be covered with a sloping metal space frame and sheathed in glass to create two triangular atrium lobbies. The ten-foot space between the towers connected the lobbies to provide diagonal pedestrian access through the block, making at least a symbolic link between the downtown office buildings to the south of the project and Houston’s cultural center and convention hall to the north.

A model of this scheme was presented to Liedtke, who liked the two-tower approach, the angles, and the sloping atrium units between the towers. But the model, at that point, had flat roofs. Liedtke said he wanted his project “to soar, to reach, and a flat-top doesn’t reach.” Johnson reportedly took one of the angled corner sections of the presentation model and set it on the roof, asking Liedtke if that was what he was talking about. And voila – Pennzoil Place was born.

Of course, a great deal of refinement was necessary after that point in order to make walls turn gracefully into roofs and to make offices fit neatly under sloped edges. But the geometric scheme turned out to be an inspired one. The final building form seems far more complex in experience than its plan would indicate. Like good minimalist sculpture, it makes visual puzzles for the viewer that are at once baffling and easy to decipher. As one moves around the building from a distance, its elements come together and then break apart, compose and recompose in a dynamic, kinetic melody of form.

The building was immediately lauded as a marriage of “the art of architecture and the business of investment construction” (Ada Louise Huxtable, “Houston’s Towering Achievement,” New York Times, February 22, 1976). It became proof to skeptical high-art architects that a developer could be an enlightened client for innovative design and proof to developers that good design could payoff in the real estate marketplace.

Well beyond its immediate economic successes, Pennzoil Place has become a vital asset for the city of Houston. It is a colossal kaleidoscopic sculpture for the city, enhancing every freeway view of downtown that catches it. It has inspired a greater richness of form and shape in the buildings which have succeeded it, not only in Houston, but around the globe. It is one of a very few Texas buildings of world-class stature which can legitimately claim to have made a significant impact on the discipline of architecture worldwide.